Lawrence Johnson spent 41 years creating what is the most famous garden of the Arts and Crafts movement and one of the most inspirational gardens of all time. Much is made of the way the garden is divided into rooms, and this has led to many gardens trying to use this technique to create a sense of space. Many invariably just end up with the opposite effect and none capture the beauty of Hidcote. This is because the garden is not about the “rooms”; it is about the vistas and how Johnson uses them to control the visitor and tie the garden into the surrounding countryside.

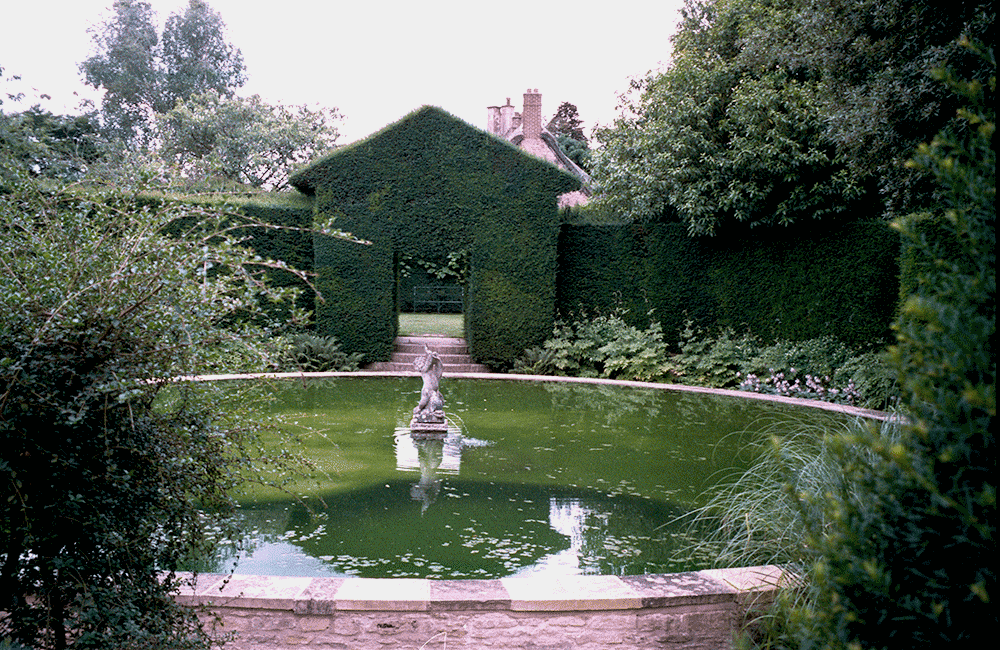

This starts when you come out of the house into the garden; the first thing that strikes you is the vista past the cedar to the stilt garden. This doesn’t run straight out from the house as gardens of early times would have, but across the back of the house running parallel to it and making the visitor turn to there right. Then by using the cedar in the foreground and a clear path out to a glimpsed of a structure in the distance the gardens creator though dead since 1958 takes you firmly by the hand and leads you where he wants you to go. The individual gardens which envelope this path act to lead you on as the view out between the pleached hedges gradually emerges. Then just as the view of the surrounding countryside crystallises before you, you catch sight through a small summer house of the Long Walk. This is a broad grass lawn which stretches all the way to the garden boundary terminating in a large pair of gates. The walk is over 200 metres long, but its scale is further exaggerated three-fold. The walk is viewed from an elevated position from the summerhouse and then falls quiet steeply for the first 40 or 50 metres before climbing gently for the remainder of its length. Over this last gently rising section the width narrows, but not so much as to be obvious to the viewer, but sufficient to heighten the sense of perspective. Finally, the walk is virtually devoid of planting with just unbroken grass enclosed by tall plain green hedging which hide the garden planting.

This use of enticing views created by enclosure is repeated throughout the garden leading the visitor at Lawrence Johnson’s command. Therefore, the rooms though at first sight may appear to form the garden are in fact the means of creating vistas in a whole range of scales and it is these which lead the visitor through the garden while never allowing them to see the full picture. This way Johnson could experiment also with different styles of gardens and ensuring you will never tire but instead lose yourself in his creation.

This garden is something of an enigma; laid out between 1907 and 1948 by Lawrence Johnston, little is understood of his gardening philosophy as he wrote next to nothing on gardening. He also created little; one small rockery and two gardens both of which were quite different in character and style. In the past, it was believed he was some sort of shy recluse, but his diaries clearly contradict this and the really reason he wrote so little about gardening was most likely that he didn’t need to. Most of the influential gardeners of both past and present needed money and garden writing was a good source. For example, Gertrude Jekyll was a professional garden design for who designing gardens and writing about them put bread on the table. Similarly, Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicholson found Sissinghurst a painful drain on their resources which her writing help to ease. Lawrence Johnson simply did not need to as he was a man of considerable private means.

An American, born in Paris and from 1900 a naturalised Englishman. In many ways Lawrence Johnson was typical of a class of people at the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century, the kind of people who inspired F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novels, living a social whorl free from work. Johnston never worked, both his parent’s families were wealthy, as was his stepfather, and his mother spent the best part of her life on the New York social circuit. Where he got his passion for gardening is unclear but after graduating with a B.A. from Cambridge he moved to Northumberland in 1898 to study farming and following this he spent a lot of time at Woodville Lodge in Little Shelford. There he created a rock garden at Woodville Lodge which still exists and in 1904 he became a fellow of the RHS which allowed him access to the societies library which he made great use of while convalescing on his return from serving with the Northumberland Hussars in South Africa.

His gardening really started in earnest with this mother’s purchase of Hidcote Manor and its farm in 1907. The reason they chose Hidcote is unknown but they both had friends in the area and there was several American expats nearby. Whatever the reason it was not because of the gardens as they amounted to very little at the time. The remarkable thing was, except for the small rockery at Little Shelford, Hidcote was his first real experience of practical gardening. He had read extensively on the subject, as his borrowing from the Lindley Library shows, but he set about the creation of the garden with no formal training and employing local men from the village. This did create problems when he finally handed the estate over to what was to become the National Trust. By 1948 he was nearly 77 years old and his declining health meant he would spend the remaining 10 years of his life at his other home, Villa Serre de la Madone, in the south of France. Clear someone was needed to take over the running of the garden and an obvious choice would have been the head gardener, but when asked Johnsons reply was that he was the head gardener and none of the staff would match up to his ability. This further exasperated a difficult transition from private garden which took many years to iron out.